Swift Method - A Practitioner's Memo

The Swift method, conceptualized by Shaun Anderson, a former pivot, was designed to assist development teams in embarking on the journey of modernizing their legacy systems, often of significant scale, into contemporary microservices architectures.

Disclaimer: I used ChatGPT to help improve the writing of this post, except this line ^_^. but the idea is mine

Introduction

“we are doing DDD without mention it to our customers.”

--Shaun Anderson

The method is detailed on his personal site. Additionally, a talk presented at the Explore DDD conference is also available here. You may discover an interesting connection between the yarn and software design from the inception of this process.

During the Pivotal Labs days, it was part of the application navigator service, along with other processes and concepts like Lean, XP, and balanced team, that helped the customer’s developer team quickly set out on the legacy modernization journey, and more importantly to help them build the right software and build it right.

There are abundant resources out there for XP and TDD, abundant resources exist, including this dedicated sites and the foundational book by its creator.

Swift Method

The Swift Method, depending on its flavor, may take anywhere from half a week to 3 weeks. The process I’ll outline here would take longer to complete; however, it should be easier to follow along for the beginners.

Goals and Anti-Goals

Although seemingly obvious, setting clear, prioritized goals and anti-goals, cast aside what isn’t a high priority at least for now, holds paramount importance for the project team.

For engagements spanning 6 to 12 weeks, it’s crucial to emphasize that objectives such as implementing the system in its entirety certainly isn’t our primary goal (an anti-goal). Conversely, while focusing on the enablement aspect, project core members will likely present divergent objectives and we should group them by themes and then prioritize accordingly.

Event Storming

Event storming entails gathering the business events occurring in and around the target system. This activity is a much simplified version of Alberto Brandolini’s event storming workshop. The facilitators should keep below in mind:

- Events has business value.

- Write events in the past tense,

- Dedicate one sticky note per event.

- Arrange events in chronological order from left to right.

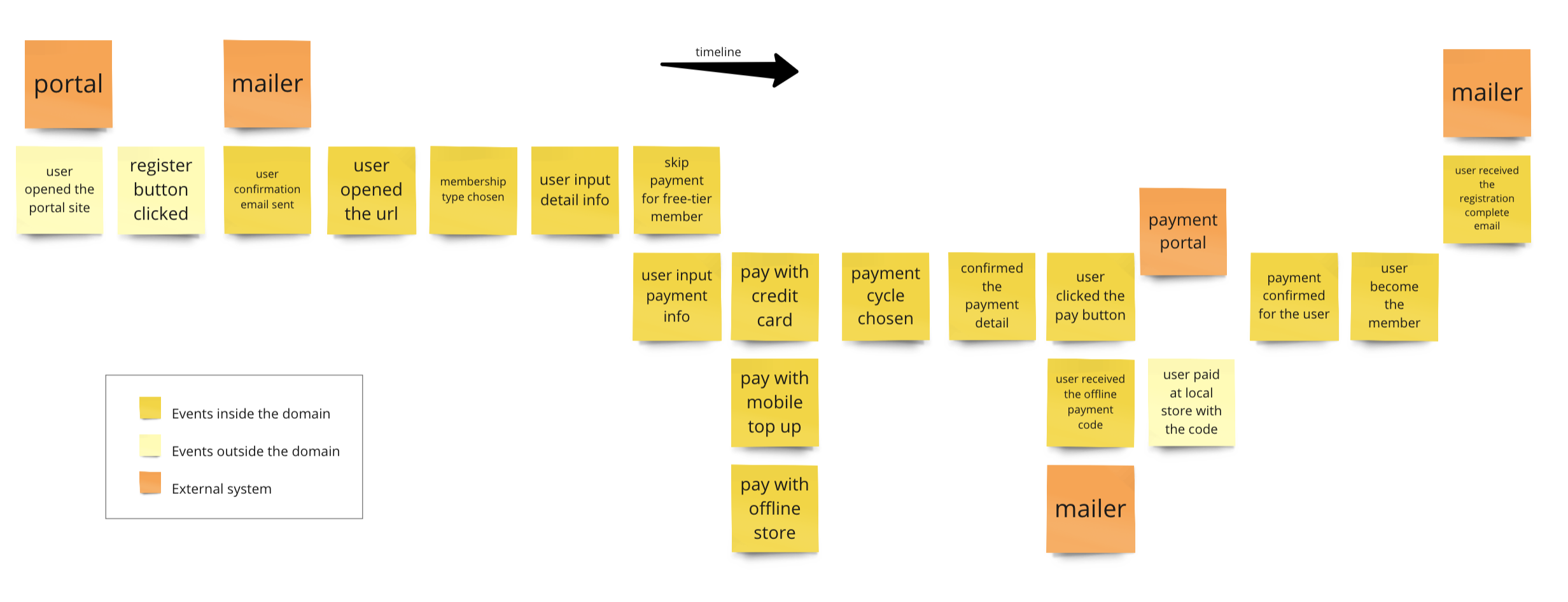

Below is an example event storming board illustrating how a user registers and optionally adds a payment method to their account.

Service Identification

After gathering the events, we should start thinking the key components of our new system.

We usually aim for collecting about 60 to 80 percent of the business events within the system. Not the full set of events, particularly for those trivial ones, unless there are issues or performance concerns in that part of the system.

To identify potential service candidates, we’ll evaluate internal and only the internal events individually, considering the business capability necessary to enable each event. Guidelines for identifying candidates include:

- Business capabilities

- Data ownership

- Loosely coupled

- Testability

When in doubt, specific criteria help determine whether it should be a microservice. The excerpts from the blog posts is listed below:

- Rate of change

- Scalability (independently)

- Lifecycle management

- Isolated failure

- Simplifying external dependencies

- Freedom of choosing other technology

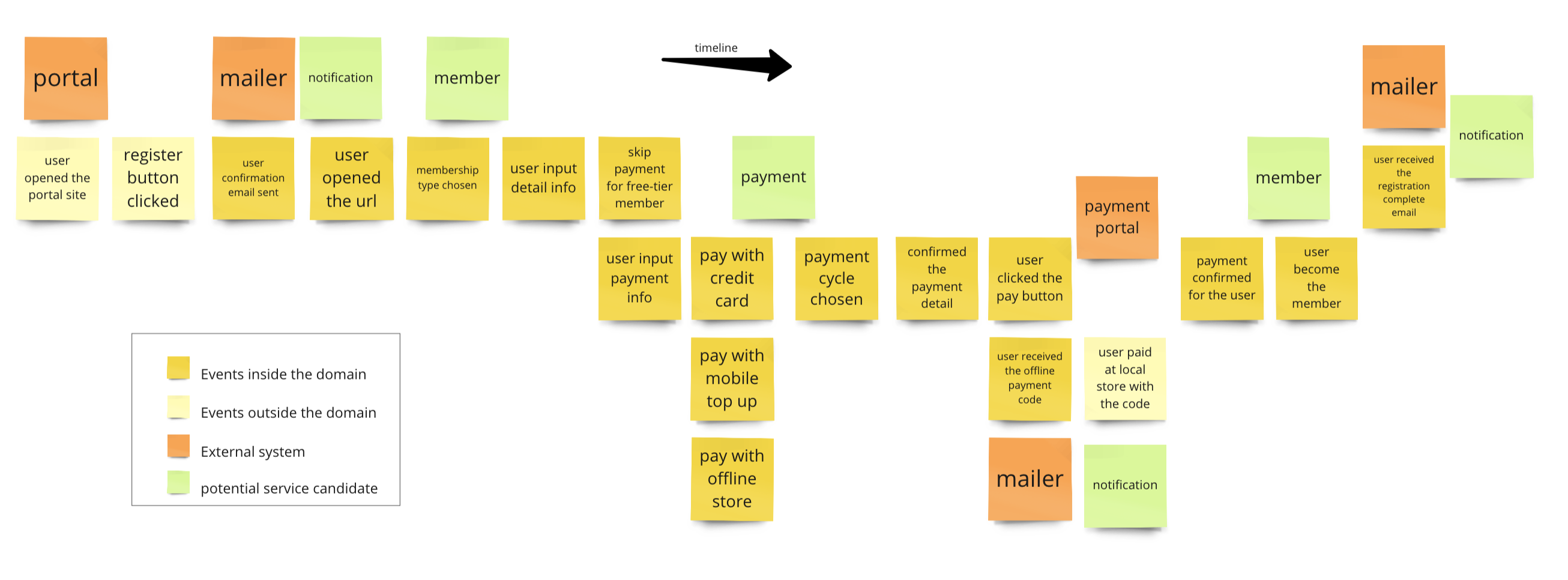

Here’s an example of the service identification results for the events collected earlier.

Boris

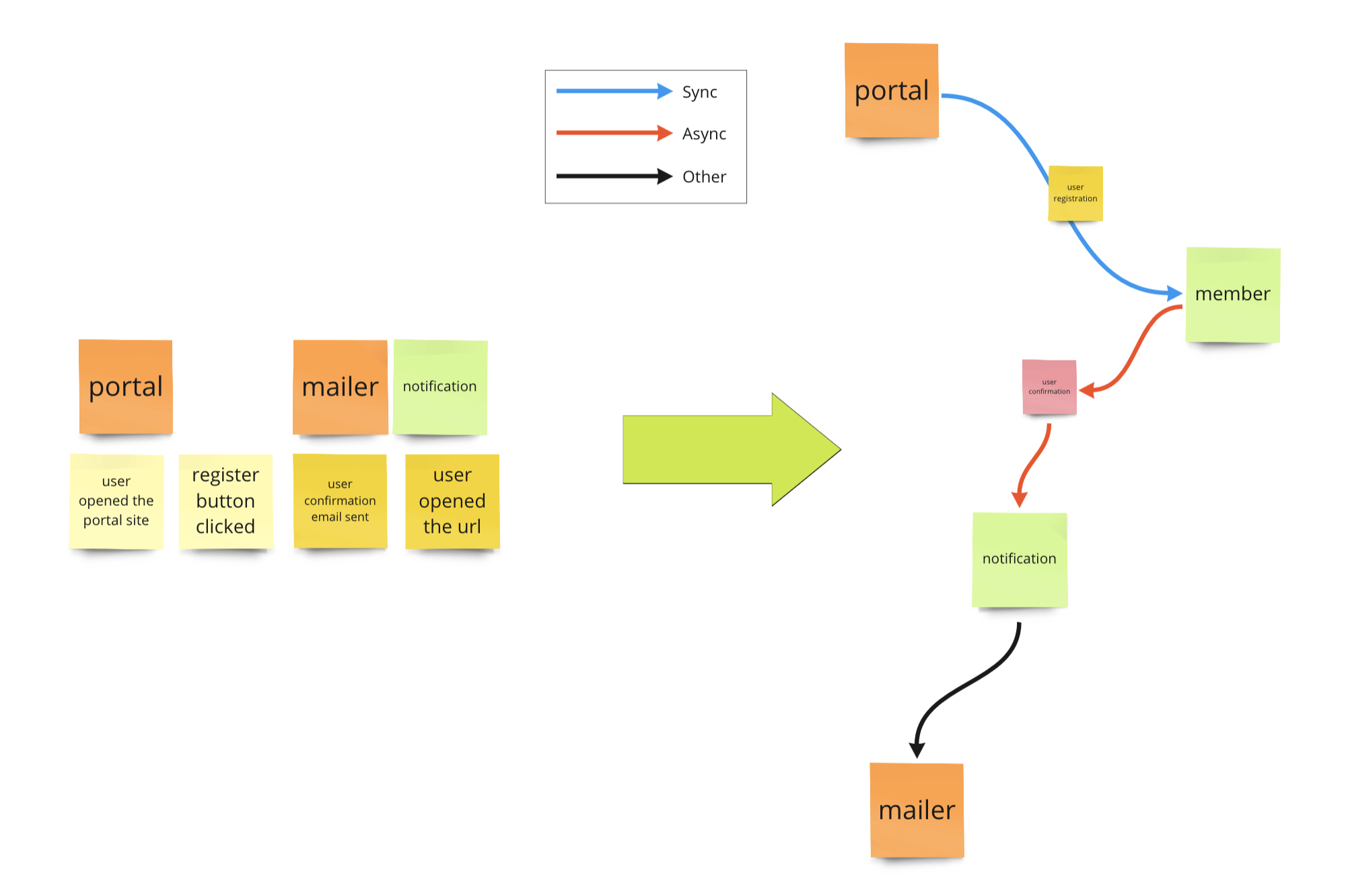

The Boris process is pivotal in the Swift Method. Here, we map relationships between service candidates following those event flows identified in previous steps, utilizing abstracted communication methods (either synchronous or asynchronous). Communication protocols beyond our control are usually marked in black and set aside.

Here’s how you transform events into the first draft of a Boris diagram, based on the first two internal events.

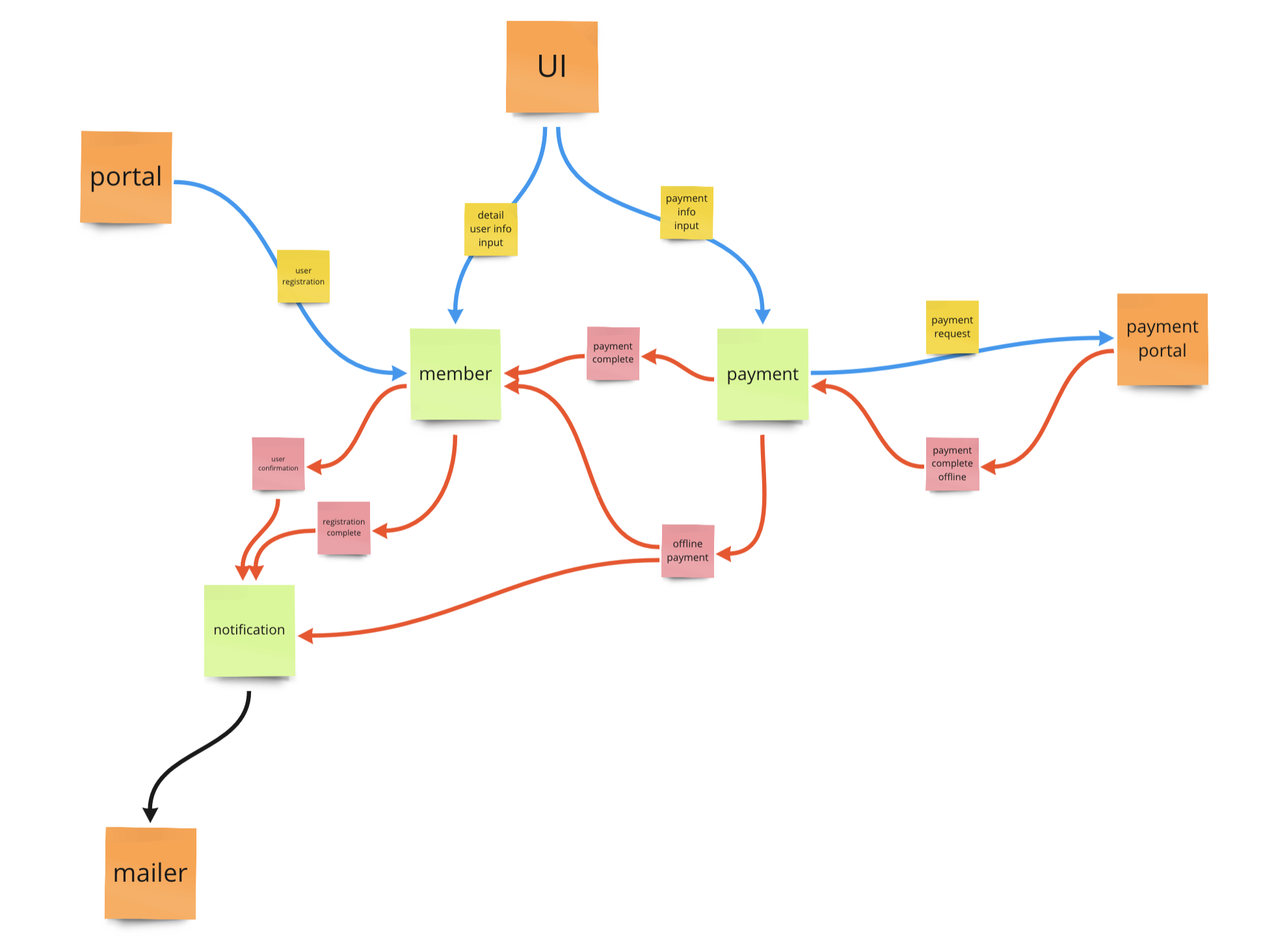

When completed the selected flow, the Boris starts resembling a spider web of the services and external systems.

When completed the selected flow, the Boris starts resembling a spider web of the services and external systems.

When crafting the Boris diagram, team discussions are encouraged to determine how events should be mapped onto the diagram. This often involves iterative back-and-forth between the event storming board and the Boris diagram. Additionally, services may undergo renaming, splitting, or merging as part of this process. It’s typical to make adjustments such as adding missing events or updating for enhanced conciseness and clarity to the event storming board too.

SnapE

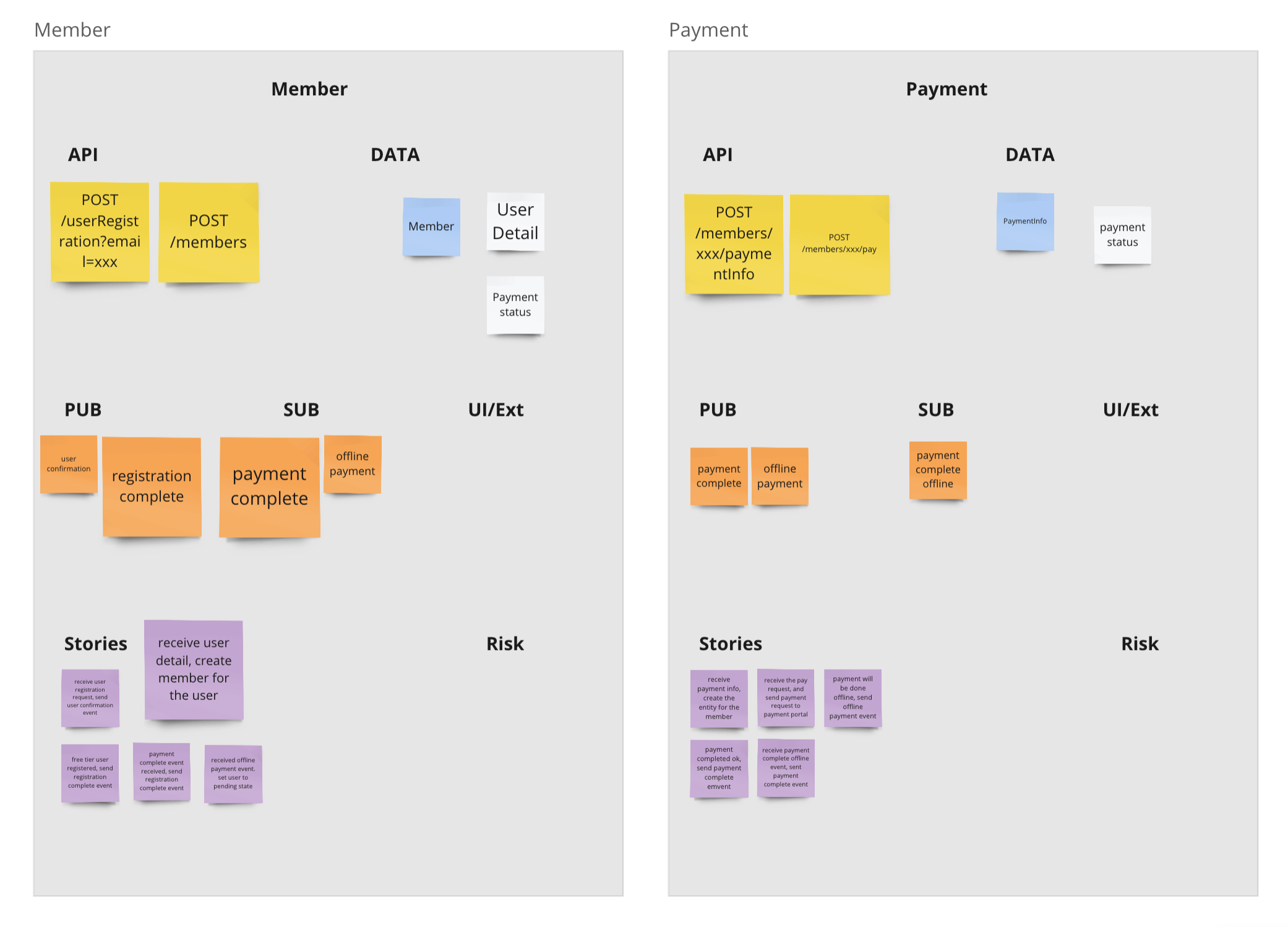

The SnapE step, with its odd name standing for “snap not analysis paralysis extended,” entails capturing the internals of each important service candidate from our Boris diagram. By now, you should understand why we refer to them as potential service candidates, as they may change, combine, or split multiple times.

When bulk part of the diagram is complete, capturing 60 to 80 percent of the flows from the event storming board, the team should gain confidence that the system (notional) architecture has taken shape and won’t change significantly.

It’s then time to document the internals of the services, capturing APIs, data, high-level stories, and risks. Here are two examples.

The activities thus far constitutes the first iteration of your Swift process. Though demanding (typically requiring full-time team involvement for the entire 3 weeks), compared to the traditional process, the Swift Method aptly matches its name.

Regarding the potential service candidates

Now that we’ve identified most of the service candidates, the team often assumes that each of these candidates will eventually evolve into microservices within the system. However, it’s premature to make such assumptions or decisions at this stage. It’s crucial to refrain from delving into implementation details too early, as premature optimization or solutioning is the root of all evil.

As per the definition of microservices, they are independent deployable units of the system. While some of the service candidates we identified could indeed become a microservice, it’s also possible for multiple candidates to be combined into one. Techniques like modulith allow for flexible application deployment. Unless we have clear insights from past experiences, there’s no need to make decisions about how to deploy the service at this early stage.

Backlog Management

Once we’ve established the initial version of our notional architecture, is it time to don our developer hats and start coding? Not quite yet.

Thin Slices

The foremost task is to select where to commence building our system. This slice isn’t a single service or multiple services but rather a slice of system functionality that cut through multiple services. It typically represents an end-to-end flow embodying a user’s interaction (that of business value) with the system. There may be multiple choices. Opt for one that is simplest or one that addresses current pain points in the legacy system, aiming to demonstrate how the new architecture can alleviate or mitigate those pains.

Even if you’re totally confident that the notional architecture you have now would solve all the issues, you should still start building the new system incrementally. Sooner or later, you’ll find situations that architectural changes is inevitable.

Backlog and IPM

Now that we’ve determined the content of the first Minimum Viable Product (MVP) for our new system, the product manager scrutinizes the slice and the features it comprises. The PM begins crafting the first batch of stories, a topic beyond the scope of this post. When ready, the PM convenes the team for the pre-IPM or IPM ritual, enabling the team to review the stories and assign a score. The score, using simple numbers such as 0, 1, 2, or 3, should reflect the complexity of it rather than the time required to develop the story.

XP and TDD

Given the abundance of available materials, I’ll forego delving into most details in this section.

However, one critical aspect the team should contemplate is the true essence of a unit test.

The original meaning of a unit test, contrary to common belief, pertains to a test that can run independently. It’s unrelated to the scope or target it tests against, as commonly understood nowadays.

This raises another question: Consider a scenario where, during initial development, your unit test covers the behavior of accepting REST requests from users and inserting that data from request parameters into the database using the repository, which was a direct dependency of the controller class.

Later, you refactor out the repository dependency and transfer it to your service class. Should you refactor this unit test to align with the changes in your production code?

While I prefer not to refactor the test cases now. I don’t have a clear answer to this questions myself.

Final Words

The aforementioned processes don’t follow a linear trajectory from architecture design, development, to deployment. Instead, they represent an iteration of the interleaving, even back-tracking of backlog refinement and coding activities.

Though not publicly advocated, our experiences have shown it has broader potential in software design in general, particularly when incorporating Lean and TDD principles.